Artificial Intelligence and Facial Recognition: Privacy, Ethics and Regulation

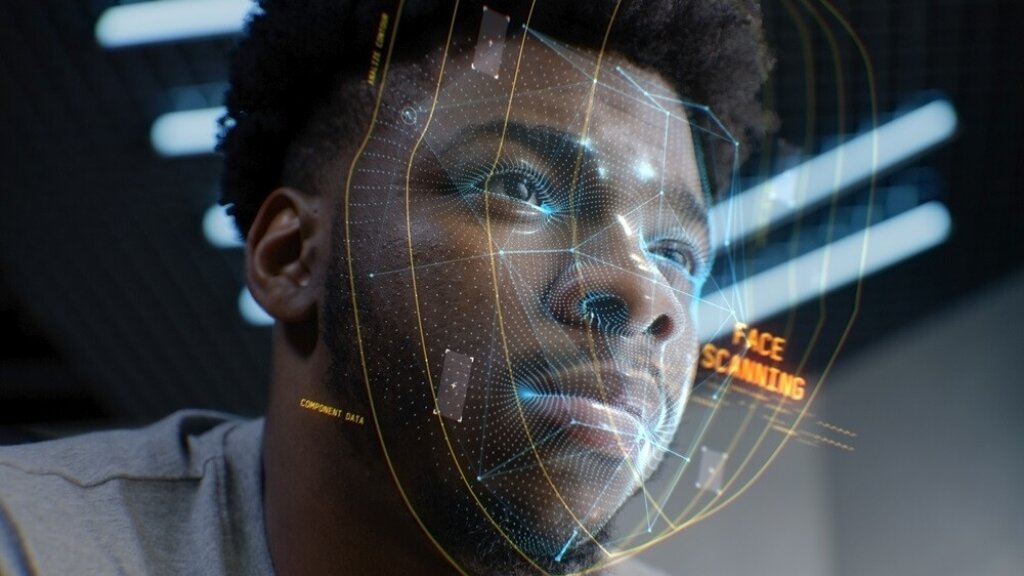

Artificial intelligence is changing how societies work, from transport to healthcare, but nowhere is its impact more visible - or more contentious - than in AI facial recognition. AI facial recognition technology, which uses algorithms to identify and verify individuals by analysing their facial features, is being rolled out across public and private life. From policing Britain’s high streets to diagnosing medical conditions, its uses are multiplying fast. But the ethical, legal and social implications are still unclear.

This article looks at the growth of facial recognition systems in the UK, the risks of artificial intelligence surveillance, the benefits of healthcare applications and the need for regulation to balance innovation with civil liberties.

The UK at the Crossroads of AI Surveillance

In September 2024 the UK became one of the first signatories to a landmark European treaty on artificial intelligence, designed to protect democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The move put Britain at the forefront of responsible AI. But at home a different story is unfolding.

The government has announced plans to expand the use of facial recognition systems in the UK, particularly in policing. Ministers say the technology can prevent violent disorder, find missing people and identify suspects. But critics point out there is no comprehensive law to govern such use. Instead, there is a patchwork of non-statutory guidance and regulation, which leaves big gaps in accountability.

Civil liberties groups have gone further and say Britain is on course to have one of the most surveillance states among democracies. This tension - between being a global leader in AI ethics and embedding AI surveillance at home - is the problem governments face in the digital age.

A Patchwork of Oversight

Currently AI governance in the UK is based on a principles-based approach. Regulators like the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) oversee some data use but there is no law specifically for artificial intelligence in face recognition. This fragmented system allows police forces and some local authorities to roll out the technology with minimal oversight.

Figures from the Metropolitan Police in London show that in 2023 over 360,000 faces were scanned during live deployments. Similar pilots have taken place in Essex, North Wales and Hampshire. Supporters say such initiatives help identify suspects quickly. Detractors say they normalise blanket surveillance, often without public knowledge or consent.

Accuracy, Bias and Predictive Policing

The technical issues with AI facial recognition add another layer of complexity. Research in the UK has found significant disparities in accuracy, with higher false positives for black individuals compared to white or Asian counterparts. This mirrors international studies that show racial and gender bias in algorithmic systems.

Beyond identification, some police forces are experimenting with predictive analytics to flag people who may commit crimes. Critics say this is a move from investigating crimes to predicting them, which is an ethical minefield. A coalition of civil rights groups have called for these systems to be banned outright, saying they are incompatible with democratic freedoms.

Surveillance and the Private Sector

It’s not just the public sphere. Private companies in the UK are also experimenting with artificial intelligence surveillance, particularly in retail and workplace management. From monitoring employee attendance to tackling shoplifting, businesses see efficiency and security.

But several cases have shown the risks. In one instance an organisation was found to have illegally processed biometric data of thousands of staff. Elsewhere schools have trialled facial recognition for canteen payments without proper data protection assessments. The ICO has intervened but its powers are limited when global corporations are involved. International firms have challenged penalties and won, leaving regulators struggling to exert control.

This blurring of the lines between state and corporate surveillance is particularly worrying for the public. Surveys show over 50% of UK citizens are uncomfortable with biometric data being shared between police and businesses, yet it’s happening.

Healthcare Applications: Promise and Peril

While the public debate focuses on policing, artificial intelligence in face recognition is also entering healthcare. Hospitals and care homes are exploring its use to improve patient safety, streamline record-keeping and secure access to sensitive areas.

Researchers are also looking at diagnostic uses. Certain genetic conditions leave facial markers which AI tools can identify faster than traditional methods. Other systems aim to assess pain in patients who can’t communicate, such as those with dementia, by analysing subtle facial muscle movements.

The benefits are significant: faster diagnosis, better patient monitoring and more efficient care. But the same issues of bias, consent and privacy apply. Studies show facial recognition tools can be up to a third less accurate for darker-skinned women than for lighter-skinned men. In a healthcare setting that’s misdiagnosis or inadequate treatment.

Events, Security and Everyday Use

Another area is event management. Conferences, concerts and sports fixtures are starting to use AI facial recognition for ticketless entry, access control and personalised attendee experiences. Organisers say it’s efficient and safe: guests can check in without physical tickets and security teams can stop unauthorised entry in real time.

The technology also collects more data and gives insights into crowd flows and session popularity. But this expansion into everyday leisure activities raises more questions. How much surveillance is acceptable for convenience? And how should the data gathered at private events be protected and stored?

Privacy, Consent and Civil Liberties

At the heart of the issue is privacy. Faces are not just identifiers, they are biometric signatures that can’t be changed if compromised. Converting them into data creates new risks, from identity theft to tracking without consent.

One of the biggest problems is consent. Many deployments happen without explicit permission from those being scanned. Unlike clicking “accept” on a website, the public has no practical way to opt out when surveillance cameras with AI are in the streets, shops or schools.

Issues surrounding consent put the onus on policymakers to create clear safeguards so individuals can control their own data.

Towards a Regulatory Framework

Given the pace of facial recognition technology adoption, many argue that the UK needs a dedicated law for facial recognition systems. This could include:

Transparency requirements to tell the public when facial recognition is being used.

Consent standards for opt-in models for non-policing uses, like retail or healthcare.

Bias audits to test and certify systems for fairness across demographic groups.

Independent oversight to create a statutory regulator to monitor across sectors.

International cooperation to align rules with global standards to prevent loopholes for multinational companies.

Without these, the UK will undermine the very rights its leaders signed up to on the world stage.

The Future of AI Facial Recognition

There’s no denying the potential of AI facial recognition. In healthcare it may revolutionise diagnosis; in events it may redefine convenience; in policing it may reshape public safety. But technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Its use reflects our values, priorities and choices.

Britain has a choice. To have the benefits without the erosion of civil liberties. Policymakers must act fast to make sure innovation is matched by accountability. As the tech becomes more mainstream the debate on privacy, ethics and regulation will only get louder.

Conclusion

AI facial recognition has big questions for the UK and the world. It offers tools to improve health, security and efficiency but it also deepens inequality, normalises surveillance and erodes democratic rights.

The task ahead is not to stop innovation but to control it. Regulation, transparency and public conversation are key to making sure technology that recognises us doesn’t end up stripping away the rights that make us.

Responsible Video Redaction to Protect Personal Data

Facit specialises in ethical video processing to protect people’s personal data. Facit’s AI-powered video redaction technology uses AI to recognise and mask features such as heads and bodies but it does not use facial recognition to identify specific individuals. Facit’s redaction software, Identity Cloak, enables users to produce and share video footage compliantly, quickly, accurately and cost-effectively.